Lecha Dodi

Echelon

Art Gallery

Oil Paintings,

Prints, Drawings and Water Colors

Lecha Dodi

© 2011 Drew G. Kopf

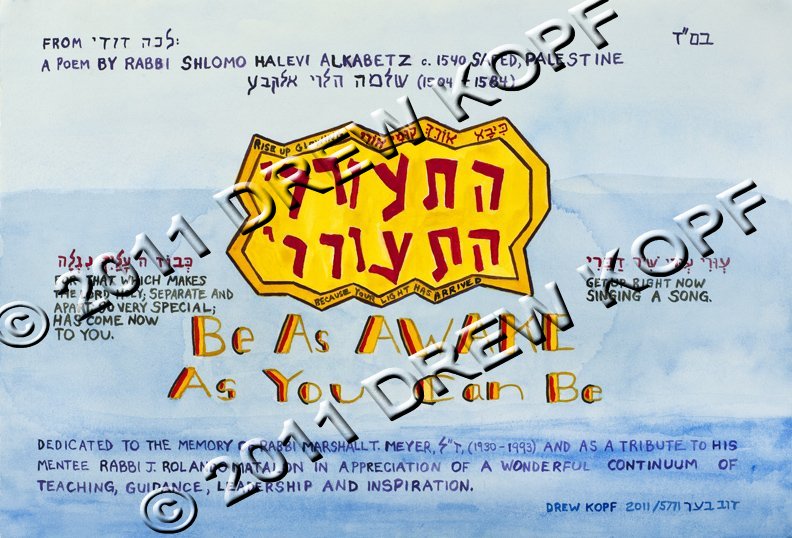

Title:“Heetoreree Heetoreree” התעוררי התעוררי also referred to as "Everlasting Freedom"

Medium: Water Color on Paper

Size: 22" x 17"

Available Framed or Unframed

Signed: Drew Kopf 2011 and דּוֹבֿ (in Hebrew) 5771 (lower right)

Created: Av 5771 corresponding to July and August 2011

Original: A gift of the artist.

The text afixed to the back of the framed origional and which is provided with each geclee copy, reads as follows:

Lecha Dodi לכה דודי |

| © 2011 Drew G. Kopf |

The Sabbath is everything. The message of Rabbi Shlomo HaLevi in his liturgical poem Lecha Dodi לכה דודי written in about 1540 goes much further than the way we use it in our Friday evening services when we sing it to wonderfully melodic tunes and turn towards the entrance door of our chapels to bow and symbolically greet the Sabbath as a new bridegroom would greet his bride. The Rabbi was using his great skill as a wordsmith and poet to create an easily memorized piece that could be brought to mind and mulled over at will by anyone, even the many illiterate Jews, who came to pray with their community when they could and who depended upon the leader of the prayers to provide them with the words for them to repeat or to simply give their assent to by answering “amen” at the appropriate time. On the Sabbath, in one sense, everything stops. But, in another sense, and perhaps more importantly, on the Sabbath, everything begins. Perhaps a nice way to look at it is by looking at what goes into the making of anything fabulous; a fabulous meal, a fabulous work of art like a painting or an architectural triumph like Fallingwater, the memorable house designed by Frank Lloyd Wright for Edgar J. Kauffman on Bear Run in Western Pennsylvania, or a fabulous theatrical event like the Cirque Du Soleil company produces all over the world to the amazement of thrilled audiences who need not know one word of any particular language to get everything there is to be gotten out of the performances they witness. The preparations for the making of these wonderments are surely feats to behold in and of themselves. They would be the stuff from which documentary films might be made. The inside story of the making of the movie “The Bible” would be tremendously interesting and revealing, but it would not be the movie itself. So, it is, “Lehavdeel”; i.e. to make a distinction between that which is Holy and that which is mundane, with the story of Creation. The Creation of the world in six days is an amazing tale with the making of man and woman to “rule over the fish of the sea and the birds of the air and over every living creature that moves on the ground” (Genesis 1:28) coming as a capstone to the story. But, if the story ended right there it would be all but meaningless and, frankly, boring. So what if there is a human being who has a helpmate and they live on an earth with all manner of plants and animals. Who cares? Nobody would care about that at all until the concept of the Sabbath gets introduced when the Creator Himself rested from the creative work he had been doing. (Genesis 2:2). Now, the story of Creation becomes interesting. It is literally the “nothingness” of the Sabbath; i.e. the “resting” from the work of Creation that makes the work; the Creation, worthwhile, and all the more exciting than if it existed forever but did nothing for anyone. It is the “ceasing from doing” by one’s own free will; the leaning away from the temptation to keep on keeping on; to tweak what you were creating with just one more little this or that, that makes what we are or had been doing even more meaningful than it could ever be without our turning away from it; at least for the expanse of a Sabbath day. That magical stopping of doing what we were doing in the exact same way that the Lord did when He stopped working on the world is what Rabbi Shlomo HaLevi was referring to when he crafted his poem Lecha Dodi לכה דודי , which has become the universally accepted way to launch the Sabbath among Jews the world over. “So God blessed the seventh day and made it holy, because on it God rested from all his work that he had done in Creation.” (Genesis 2:3). The Rabbi’s words are very special and, as is so often pointed out to those who might not notice it, the first letter of each line taken together spells out the Rabbi’s name, which was a popular thing for poets to do when writing such pieces. Translating his words, however, offers an interesting hurdle to be scaled. The desire to maintain the lyrical quality of Shlomo HaLevi’s poem is a natural and obvious objective so that those unable to know the nuance and flavor of the Hebrew could enjoy a rhythmic replica in English. But, often, what can be lost in a translation that tries to be faithful to the form of a literary creation is the clarity and scope of the author’s message. Though the translations found in many of the prayer books are quite beautiful and make a great effort to capture the lyrical flow of the Hebrew phrases, they may make the meaning of the poem far more cryptic than Shlomo HaLevi had intended it to be. Surely, he wanted his verses to be as clear as day and would have left nothing to be figured out or inferred. The images he chose were selected because they were very well known. The references he made are to Biblical passages that would have been instant reminders to anyone who had been raised in a Torah centered society. That said, a question that comes to mind is, “If the poem was intended for those who already knew what the message of the poem would be, then why did he feel the need to write it?” Without delving deeply into the times in which he lived, we can know that the draw of the non-Jewish and non-observant part of the community was the same, if not greater, as it is today. It is easy to become so subsumed in one's work-a-day world that one does not realize that one is becoming a slave to his own creations. When the world and what we are doing in it becomes more important to us than we are to ourselves; when we stop taking time off to demonstrate, not to others but to ourselves, that we are free, then, we are no longer free. Shlomo HaLevi must have wanted to serve as what might be called a cheerleader for the Lord; really, a cheerleader for us to act in the way that the Lord acted when he demonstrated what being free is and how important it is that even He, the Lord Himself, took a break from all he had done, called it good, and hallowed the time he took by stopping and, in doing so, created the concept of the Sabbath Day. Dare we ignore that? Shlomo HaLevi did not want the people in his community to miss out on the gift of all gifts; the Sabbath, which defines life and, without which, life would hardly be worth living. The following translation of Rabbi Shlomo HaLevi’s poem Lecha Dodi לכה דודי is anything but lyrical or poetic in the way that the Rabbi’s Hebrew is. It is offered for those of us who may not be as or at all familiar with the concepts to which the Rabbi was referring in his marvelous piece. We hope this translation helps to illuminate his words, which were written over 500 years ago, and, at the same time, help achieve Shlomo HaLevi’s overarching goal, which we believe was to keep his fellow Jews on the pathways of the Torah through the observance of the Sabbath. The Sabbath is everything. Av 14, 5771 corresponding to August 15, 2011 © Drew Kopf 2011 Lekhah Dodi דודי לכה Chorus: Line 2: p'nei Shabbat neqabelah פני שבת נקבלה Verse 1: Line 4: Hishmianu El hameyuḥad השמיענו אל המיחד Line 5: Adonai echad ushemo echad יי אחד ושמו אחד Line 6: L'Sheim ulitiferet v'lit'hilah לשם ולתפארת ולתהלה Verse 2: Line 8: ki hi maqor haberakhah כי היא מקור הברכה Line 9: merosh miqedem nesukhah מראש מקדם נסוכ Verse 3: Line 12: Qumi tze'i mitokh ha-hafeikhahקומי צאי מתוך ההפכה Line 13: Rav lakh shevet b'eimeq habakha רב לך שבת בעמק הבכא Line 14: v'hu yaḥamol alayikh ḥemlah והוא יחמול עליך חמלה Verse4: Line 16: Livshi bigdei tifartekh ami לבשי בגדי תפארתך עמי Line 18: Qorvah el nafshi g'alah קרבה אל נפשי גאלה Verse 5: Line 20: Ki va oreikh qumi ori כי בא אורך קומי אורי Line 21: Uri uri shir dabeiri עורי עורי שיר דברי Line 22: K'vod Ado-nai alayikh niglah כבוד יי עליך נגלה Verse 6: Line 24: Mah tishtoḥai umah tehemi מה תשתוחחי ומה תהמי Line 25: bakh yeḥesu aniyei ami בך יחסו עניי עמי Line 26: v'nivnetah ir al tilah ונבנתה עיר על תלה Line 28: V'raḥaqu kol mevalayikh ורחקו כל מבלעיך Line 30: Kimsos ḥatan al kalah כמשוש חתן על כלה Line 32: V'et Adonai ta aritzi ואת יי תעריצי Line 33: Al yad ish ben Partzi על יד איש בן פרצי Line 34: V'nismeḥah v'nagilah ונשמחה ונגילה Verse 9: Line 36: Gam b'simḥah uvetzahalah Line 37: Tokh emunei am segulah תוך אמוני עם סגלה Line 38: Boi khalah boi khalah בואי כלה בואי כלה

Notes on my painting "Hitoreri Hitoreri" The focus of my painting entitled “Hitoreri Hitoreri” התעוררי התעוררי are those words painted in a stylized red font which I would have flashing in the way of a strobe light if I could find a way to capture that “look” or effect on watercolor paper. Hitoreri Hitoreri are the first two words of the Fifth Verse of Lecha Dodi לכה דודי the liturgical poem by Rabbi Schlomo HaLevi, who lived in the 1500’s. The verse reads as follows: Verse 5: Line 20: Ki va oreikh qumi ori כי בא אורך קומי אורי Line 21: Uri uri shir dabeiri עורי עורי שיר דברי Line 22: K'vod Ado-nai alayikh niglah כבוד יי עליך נגלה The essence of the Rabbi’s message is expressed here with great, no, with tremendous force. He directs us, using the imperative or command form of the verb awake but in the tense that should be translated as “to be awake” or, “be awake” rather than simply “wake up” as it is usually defined. In Hebrew, I believe it is referred to as the Hithpael (reflexive; i.e. “to be awake) which would make the proper translation of the word Hitoreri in the imperative: “Be Awake. That would be true for the word Hitoreri התעוררי when it stands alone. But, the poet repeated the word, which introduces an entirely new dimension, which has a great effect on the meaning. Repeating a word in Hebrew serves to augment it rather than to merely ask the reader to say it twice. In this instance it has the effect of commanding the listener to “Be as Awake as You can Be” but more emphatically than that; “Hitoreri Hitoreri” התעוררי התעוררי : “Be as awake as you can be and stay that way; stay awake and aware,” which is what Shlomo HaLevi communicated to his contemporaries, who would have known exactly the power of the message he was trying to convey. That is why I made these words as prominently displayed as I did in my painting; to try and “shake them up a little” and thereby shake the viewer up to help the viewer appreciate the importance and urgency of the Rabbi’s message. The painting’s blue background was made in an effort to make the moments just before creation actually began come to the mind of the viewer; when sky and sea were an amorphous mass not really one or the other or both but ready to be defined further by the addition of the land. In that moment, the plan was for the next six days to be used to create the world culminating with the creation of man and his helpmate, woman. When the six days of Creation were done, the Lord would stop, rest from all He had done and evaluate his efforts. In doing so, i.e. in resting, he would create what would be the crowning glory of his entire masterpiece; the Sabbath. In creating the Sabbath, the Lord would then have given all that He had made a purpose for its continued existence: to provide mankind with a world in need of the perfecting that only mankind could bring about, and, at the same time, the opportunity for man and woman to relate to God, their Creator and the Creator of the world he made for them, to interrelate in a mutuality of love. It is the Sabbath that we greet each week when we sing the last stanza that serves to remind us of the Creation and He who is the Creator of all creators and of the freedom we enjoy to rest as He rested and, thereby, it allows us to relate, even only if in a small way, as one creator to another with the Lord our God. In our busy and, at times, frenetic lives, it is very easy for us to miss such moments. That is why I believe Shlomo HaLevi came with his imperative: “Hitoreri Hitoreri” התעוררי התעוררי to implore his listeners to “Be as awake as you can be and stay that way; stay awake and aware.” so, that they would remain vigilant with themselves to make certain that they kept all that they did in perspective by keeping the Sabbath as the focal point of their lives. I believe that were Rabbi Shlomo HaLevi here with us today, he would be alerting us with the same imperative he issued 500 years ago; to make the Sabbath the beginning, the end and the center of our week because, by doing so, we will be protecting and preserving our freedom, which will make the lives we live meaningful and worthwhile. |

| January 18, 2019 - The Jewish Post "Martin Luther King Freedon Edition" included an article by Drew Kopf detailing what inspired the making of this painting, which he also refers to as "Everlasting Freedom." Click HERE to see the article. |

Price

per Giclee Reproduction on Water resistant Canvas or 310 Gram Hahmemule Art Paper |

||||||

Size |

1 |

2

to 3 |

4

to 7 |

8

or more |

Standard Stretching |

Standard Stretching |

| 5" x 7" | $175.00 |

$150.00 |

$100.00 |

$70.00 |

custom |

custom |

| 8" x 10" | $225.00 |

$170.00 |

$135.00 |

$100.00 |

custom |

custom |

| 11" x 14" | $275.00 |

$225.00 |

$190.00 |

$150.00 |

custom |

custom |

| 12" x 16" | $325.00 |

$275.00 |

$200.00 |

$175.00 |

custom |

custom |

| 16" x 20" | $375.00 |

$300.00 |

$225.00 |

$200.00 |

custom |

custom |

| 18" x 24" | $425.00 |

$350.00 |

$275.00 |

$225.00 |

custom |

custom |

| 20" x 24" | $475.00 |

$375.00 |

$300.00 |

$250.00 |

custom |

custom |

| 20" x 30" | $525.00 |

$400.00 |

$350.00 |

$300.00 |

custom |

custom |

| 24" x 30" | $600.00 |

$525.00 |

$475.00 |

$400.00 |

custom |

custom |

| 24" x 36" | $725.00 |

$625.00 |

$575.00 |

$500.00 |

custom |

custom |

| 30" x 40" | $850.00 |

$750.00 |

$675.00 |

$600.00 |

custom |

custom |

| 32" x 48" | $900.00 |

$800.00 |

$725.00 |

$625.00 |

custom |

custom |

| 36" x 48" | $975.00 |

$850.00 |

$775.00 |

$675.00 |

custom |

custom |

| 40" x 50" | $1,350.00 |

$1,200.00 |

$975.00 |

$875.00 |

custom |

custom |

| 40" x 60" | $1,800.00 |

$1,500.00 |

$1.300.00 |

$1,175.00 |

custom |

custom |

| Please Note: | ||||||

| 1. Prices are exclusive of shipping and handling charges, which will be added. | ||||||

| 2. Deliveries to NY, CT or NJ are subject to applicable Sales Tax. Please provide Resale or Tax Exempt Certificate with Purchase Order. | ||||||

| 3. All sales are subject to the conditions delineated in the Terms of Agreement for Sale and Transfer of a Work of Art. Please print and complete a for and submit it with purchase order. Thank you. | ||||||

| 4. Prices are for printing on canvas or on 310g archival art paper. unframed pieces. Please inquire if framing is desired. (646)998-4208 | ||||||

| Abstracts | Drawings | Oils | Still Lifes |

| Architecture | Jewish Subjects | Pastels | Water Colors |

| Books | Landscapes | Portraits | |

| Cityscapes | Nautical | Prints | |

Toll-Free Phone: (800)839-2929

Toll-Free Fax: (888)329-6287

| Echelon Artists | About Echelon Art Gallery | Drawings |

| Oil Paintings | Water Color Paintings | Prints |

| Exhibitions | Art for Art Sake | Helpful Links |

| Interesting Articles | Photographs | Pastel Paintings |

| Artists Agreement | Purchase Art Agreement |

| Geoffrey

Drew Marketing, Inc. |

|||||||

|